I'm firmly in the genre camp. I write great stories that I like to read, without consideration of whether they will endure for the ages. Now, just because I write genre fiction does not mean my books should not be considered literature. Some of the greatest authors ever wrote genre fiction. I was reared on a healthy diet of Sir Walter Scott, Jane Austen, Tolkien, and hundreds of other luminaries. I also devoured books by non-noteworthies and enjoyed them as well. Romance, adventure, thriller, mystery, historical, biographical, fantasy, science fiction, oh my goodness, the list goes on and on - I've read and loved them all.

But we've arrived at the point I'd like to consider. What defines genre? Or, is the correct question, who defines genre? One of my fellow Cogwheel Press authors recently objected when I suggested his book might appeal to readers of Christian speculative fiction. Whereas I was using the term in a general sense (speculative fiction is any kind of story in which the author has created an imaginary universe in which the laws of nature, physics, chemistry, etc. from the "real" world don't necessarily apply), my friend cautioned against including him and his work into a genre that is defined by a particular reader segment's expectations of content. In this case, "Christian speculative fiction" ceases being a general adjectival description and becomes a brand. A brand carries with it an implicit promise that the product behind it will behave in a predictable way.

So for example, if I were a "cozy mystery" writer, I'd be producing stories of a certain length (usually fairly brief) with certain kinds of characters (think Murder She Wrote) and certain kinds of action (nothing graphic or messy, and all the plot threads get tidied up in the end). I'd be following a set of implicit, amorphous conventions that have generally been upon by my target audience segment, and, importantly, by the publishers who service that market segment.

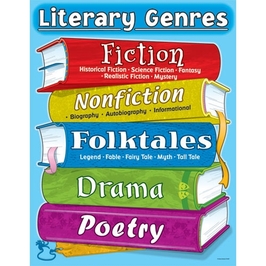

Genre allows fiction to be placed into buckets and organized in a kind of Linneic system of taxonomy. "Literary" and "genre" are kind of equivalent to "invertebrate" and "vertebrate." Of course, we need genres (such as "mystery") and sub-genres ("cozy") and even sub-sub-genres to further divide and categorize the fiction species. New writers often have a great deal of trouble figuring out their genre, or where their stories fit into this system. Doing so is critical if one is pursuing publishing, but the conventions of a genre can be stifling when they feel imposed, rather than assumed voluntarily. From the writer's perspective, the good news is that there are now so many sub-sub-genres that you'll probably find one you're happy with. The bad news is that there are so many sub-sub-genres that you'll probably feel overwhelmed. And if you try to wedge a story into the wrong genre, it may not fit.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed